Visiting the Grant Museum of Zoology in London

Australian Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) exhibited at the Grant Museum of Zoology | Credit: Talita Bateman

In December 2019, I visited the Grant Museum of Zoology in London with a couple of friends and given our current situation, I thought it would be a good time to write about that visit and daydream about my next one!

The museum was established in 1827 by Robert Grant as a teaching collection for UCL. It was then called ‘The Grant Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy’ but after WWII, detailed comparative anatomy ‘fell out of fashion in zoology’, as described by the museum, and biochemistry, genetics and physiology became more prominent areas of study. Today, however, the museum prides itself in being the last surviving university natural history museum in London.

Robert Grant (1793-1874), himself a comparative anatomist and transmutationist, was born in Edinburgh and is famous for his work with marine invertebrates such as sponges (Oxford Dictionary of National Biographies, 2005).

The museum is fairly famous for including in its collection the world’s rarest skeleton, the quagga (image on the left below) and other significant specimens such as dodo bones and thylacine specimens (image on the right below).

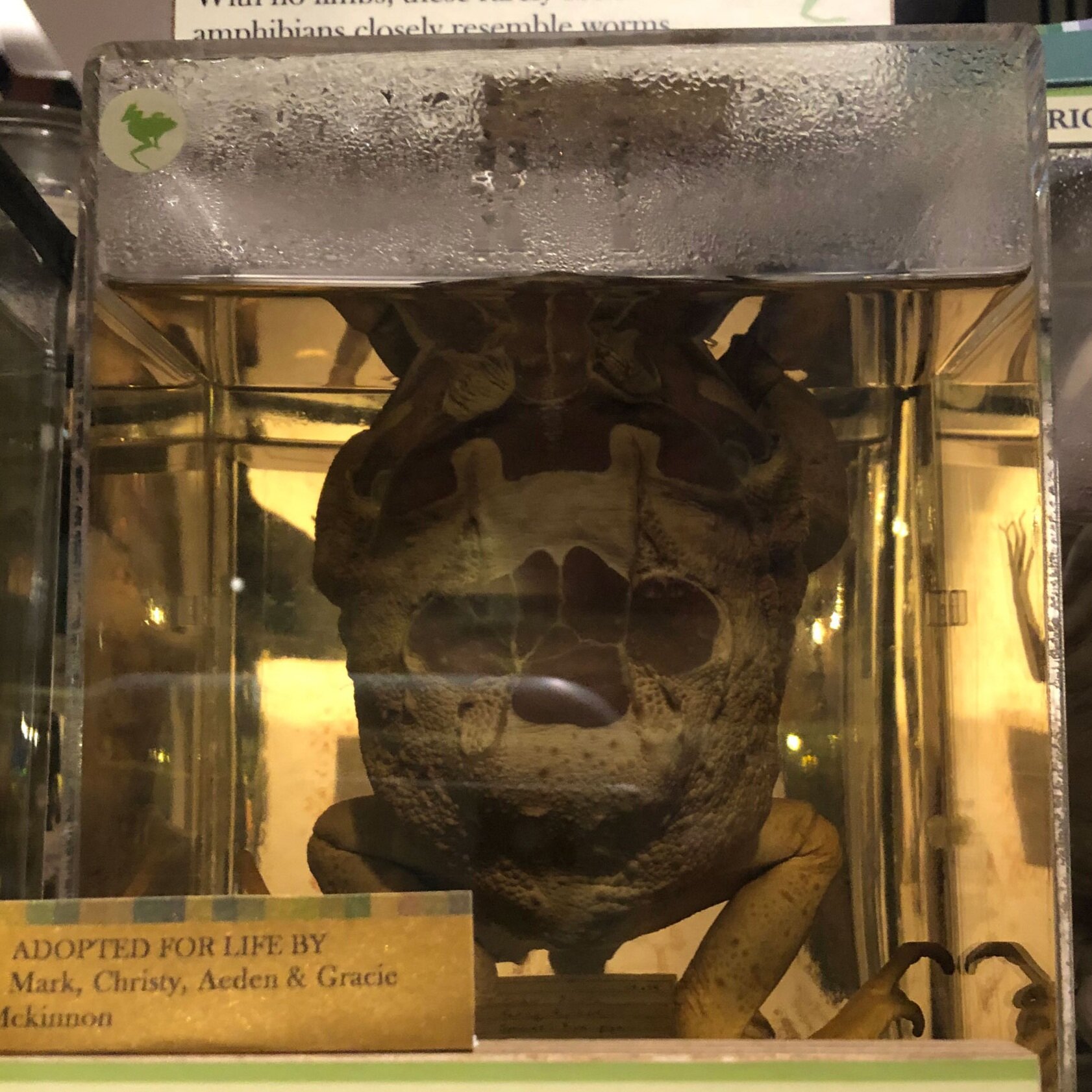

However, what makes this museum stand out in my books is their wet collections - more specifically, the fact that they include bisected mammal specimens in their displays. In his book ‘Animal Kingdom: A Natural History in 100 Objects’, Jack Ashby touches on a few examples of these displays and how museums need to be sensitive to public sentiment regarding some animals. For instance, the museum includes a bisected domestic dog head as well as a bisected domestic cat’s full body - both of which are fairly controversial with the general public and for which the museum has received quite a few complaints. Unsurprisingly, however, there aren’t nearly as many - if any - complains about other wet collections such as the bisected crocodilian head shown in the image below.

Bisected crocodilian head on display at The Grant Museum of Zoology | Credit: Talita Bateman

Speaking of their wet collection, here are a few snaps of the herpetological highlights from my visit:

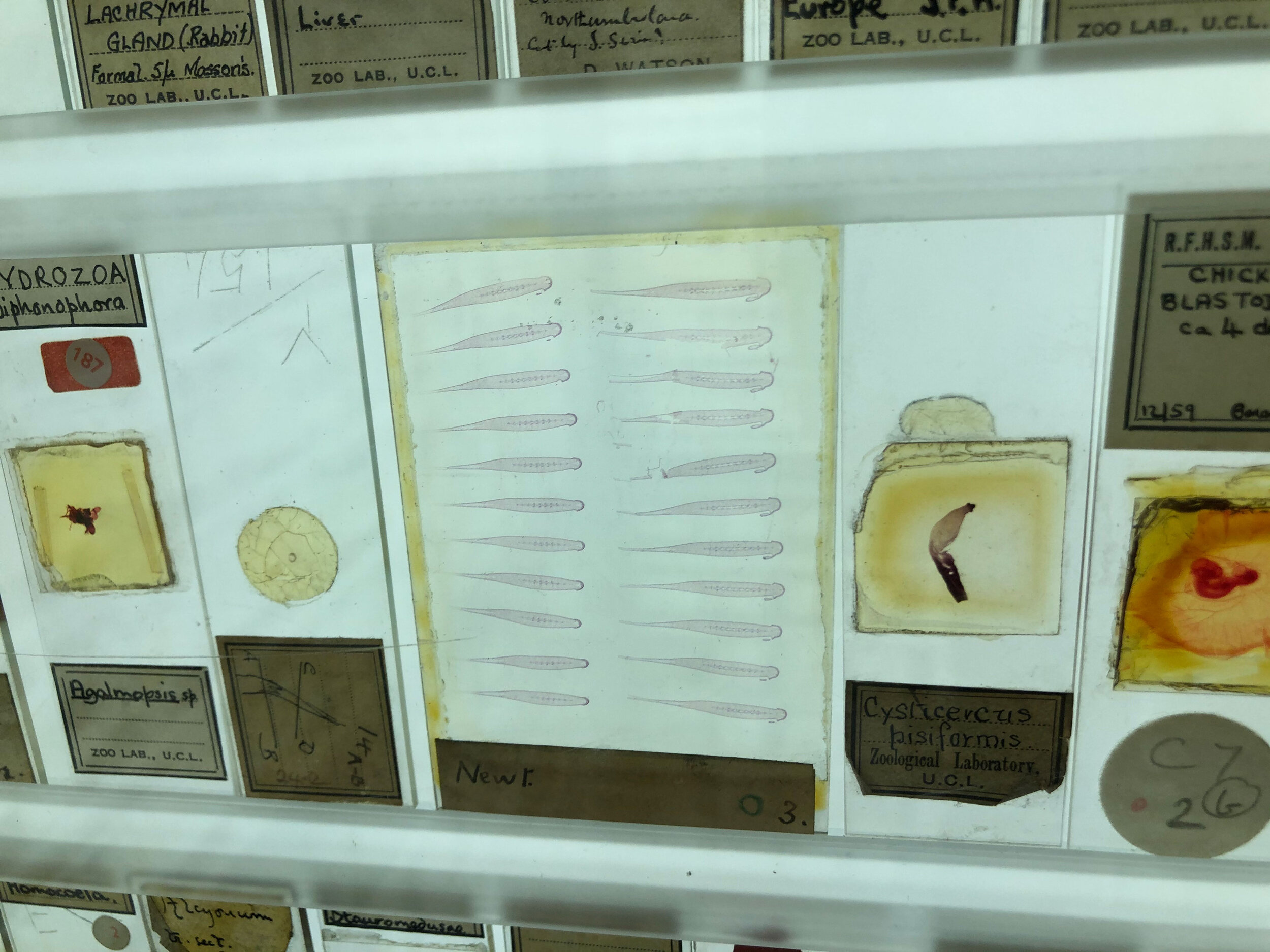

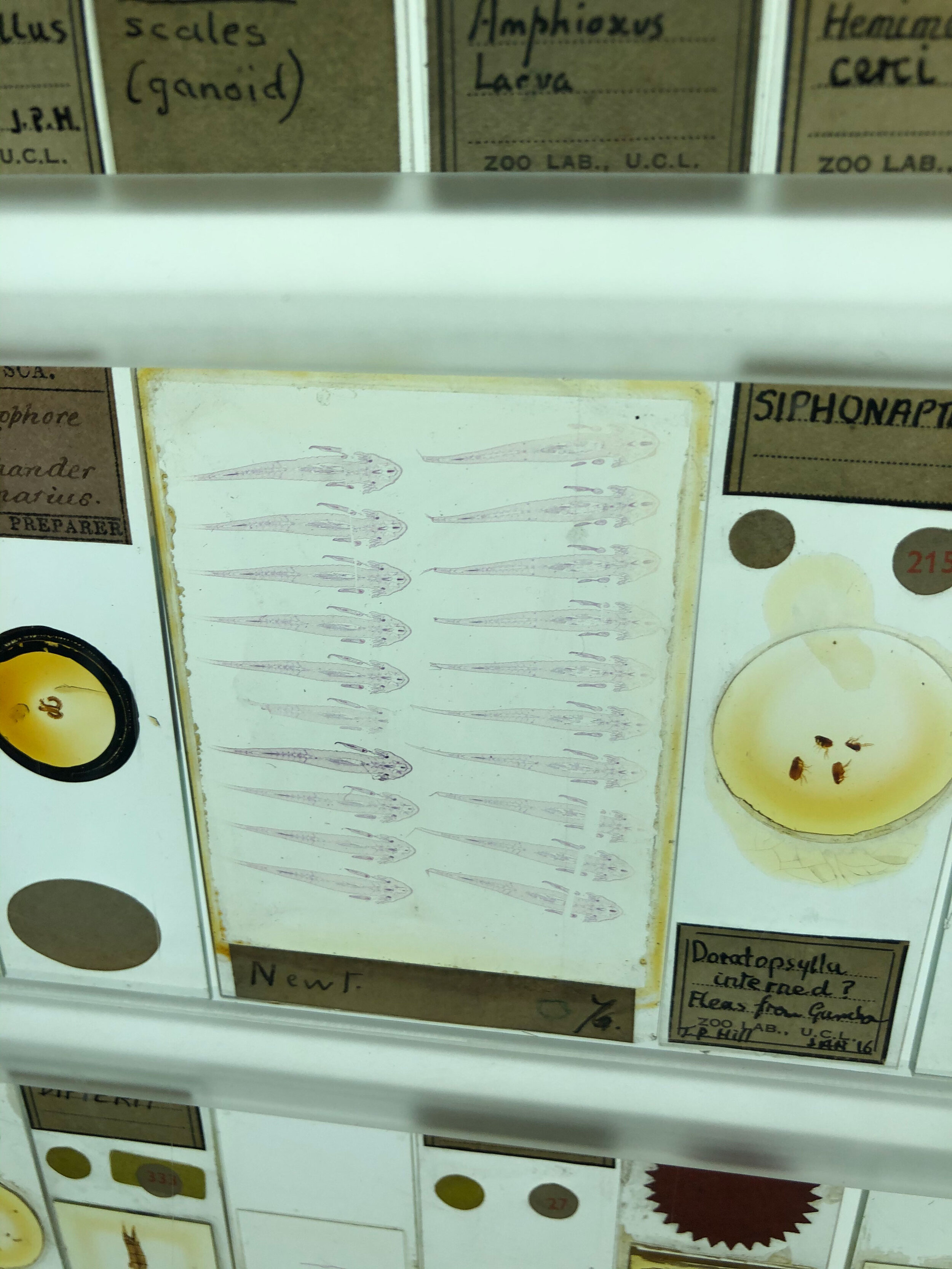

Lastly, one of my favourite displays at the museum is the Micrarium, which they aptly describe as ‘a place for tiny things’. The Micrarium aims at shedding light (quite literally!) on some of the smallest animals with about 20,000 microscope slides of different species. The two images below show slides of newts at different life stages and the last photograph displays a British human herpetologist specimen looking for herp related slides (shout out to my friend Steven Allain).

Steven Allain at the Grant Museum of Zoology in London | Credit: Talita Bateman

References:

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi-org.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/10.1093/ref:odnb/11286 . (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)